Over the past years, I've abandoned full drawings of my new chairs in favor of thumbnail sketches. The techniques that I developed for getting the chair together have gone a long way for me. Now curves of all sorts and in all places don't intimidate me, but as I honed the geometry of the pieces and wanted to set them "in stone" as it were, I heard the drawing board calling.

Above are some of the tools that I use to draft my chairs. Before I go any further, I know that I should probably get this out of the way. Yes, I know about Sketch Up, Cad, Solidworks etc... and agree that they are amazing. If I didn't think so, I probably wouldn't be paying someone $150 an hour for drawings of the new Caliper parts! But I've been drawing since I was a kid and its one of my most pleasurable and productive habits, so for now, I'm sticking with it.

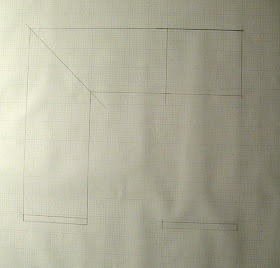

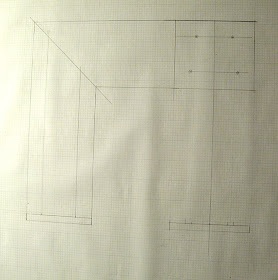

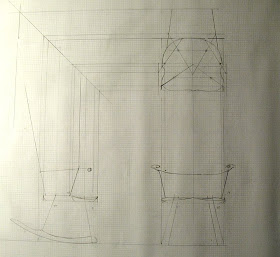

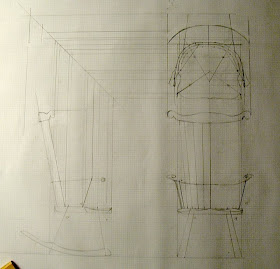

Below is the basic look of the three view drawings that I use to render the chairs. Of course this is a sketch to get the point across, the actual point to point drafting will come later along with a fourth view that is incredibly useful.

I'm going to cover a technique that I use for mapping the angles for drilling the legs. The most common way of referring to these angles is the rake and splay. Rake is the angle that the legs projects when viewing the chair from the side, splay is the angle that the legs project when viewed from the front.

One important fact that will help out later is to note that both angles share a "Common Rise" which is the length of a line dropped straight to the floor from the top of the leg. The rake and splay are great information, but most chairmakers that I know prefer to distill this information into something a bit more manageable.

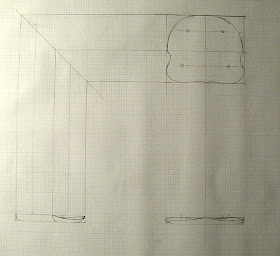

Below is the overhead or plan view of a sightline. The sightline shows the plane that is perpendicular to the seat bottom and travels through the center of the leg. When you look at this plane from the side, the leg cants at an angle that is neither the rake or splay, but when the chair is viewed from the front or side, the rake and splay will be correct.

One simple way to "get" the sight line is to turn a chair in front of you until the leg looks perpendicular to the floor, now you are staring down the sight line.

Now this may seem like an unnecessary complication, I mean, you know the two angles, why not just drill them with two bevel squares set parallel to the front and side of the seat?

The beauty of using the sightline and drilling the leg at what is called the "resultant angle" is that it reduces one of the angles to 90 degrees. Not only are we surrounded by lines that are vertical (think door jambs etc...) but we all have an innate sense of what is upright, otherwise standing, drinking, and walking would be quite problematic.

It's also helpful because it frees us from the front and side views and allows each element in the chair to be seen for the one deviation that it has along a vertical plane, which becomes even more important when we talk about curves later.

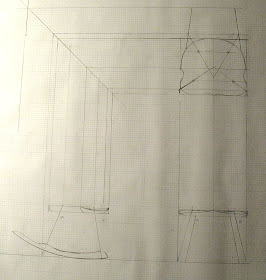

To translate the rake and splay angles from a drawing or known numbers, start by drawing the horizontal and vertical axis on the paper.

Then, measure off a common distance for the "Common Rise" on the axis. The actual length doesn't matter so long as they are the same.

Also draw the rake angle below the horizontal axis and the splay to the right of the vertical. I included the sketches of the chair to help the significance of the lines make more sense.

Then draw a rectangle that has the length and width of the rake and splay distances along the axis.

And finally, draw a diagonal from across the rectangle, this is the sight line angle.

This angle is used by connecting the two front legs (or rear) by a line on the seat blank (or pattern) and then using the sight line angle to mark the sight line.

Hopefully, the drawing below will help clarify what the line means in the chair.

So this is one piece of information, next it's a short step to getting the resultant angle.